Malware Detection Engine

Malware Analysis, Machine Learning

DISCLAIMER: This project deals with the procurement and analysis of live malware. What is presented is solely for education purposes, as part of the coursework required by my degree. I do not support malicious actions of any kind.

Project Summary

Dataset Creation

HoneyPot VM Setup

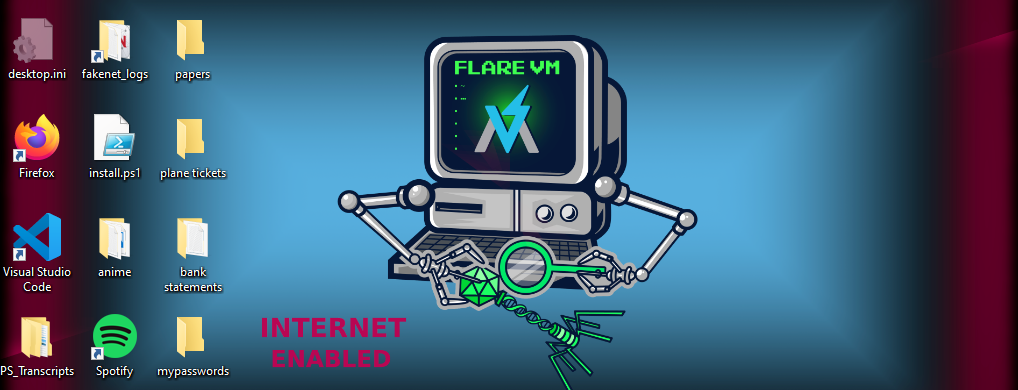

Flare VM is the most popular tool (or, rather, suite of tools) for Malware Analysis. The following guides [1, 2] were followed to the letter to prepare the analysis environment (a Windows 10 VM). Sophisticated malware has the ability to detect virtualized and sandboxed environments. Hence my first step should be to make the Flare VM seem like a normal machine than a VM. To achieve this, I just downloaded random applications, as well as created and populated random directories with sample documents. This can be seen in Figure 1. I also wanted to customize the wallpaper, but the option is disabled. I also increased the number of processors to 4 and memory to 8GB in case there are malware that take them into account.Collecting Benign and Malicious Samples

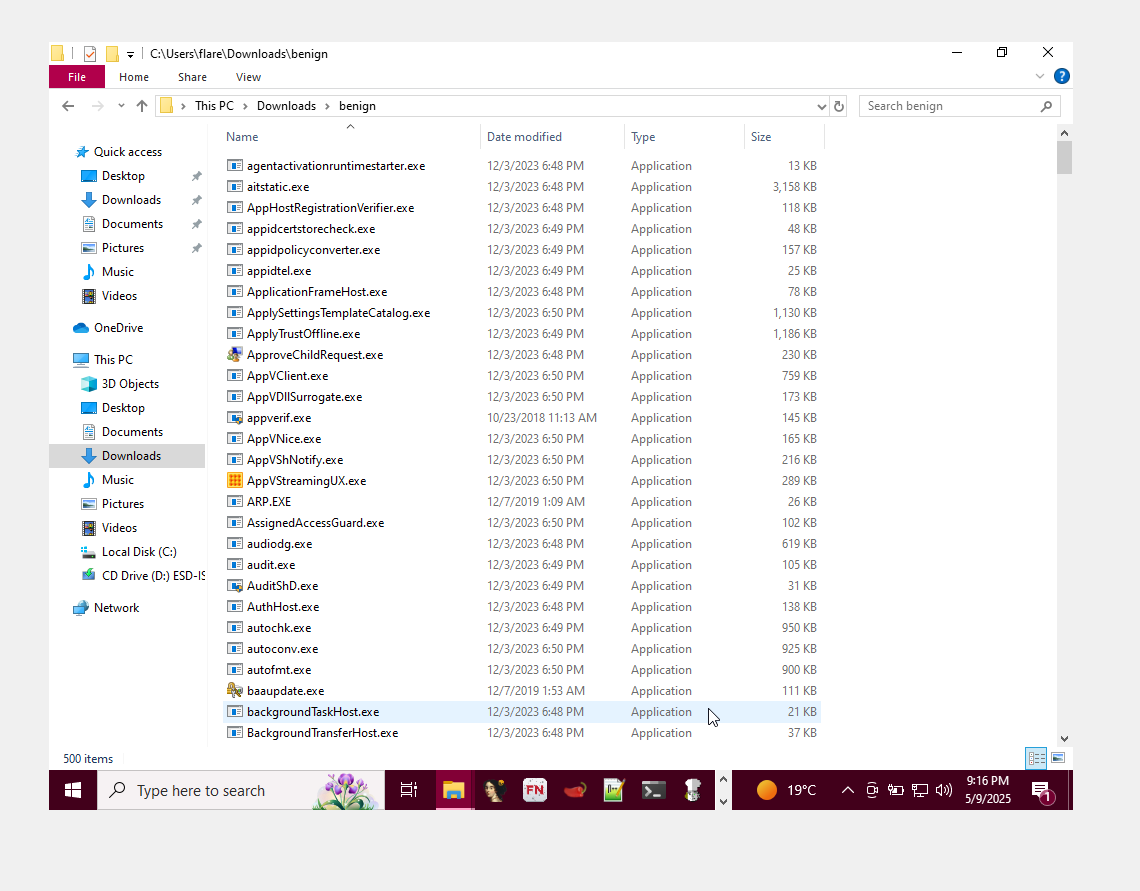

Benign executables were sourced from the Windows VM in a state prior to having any malware installed. PowerShell was used to automate this:

PS C:\Windows\system32 > Get-ChildItem -Path "C:" -Filter *.exe -Recurse | Get-Random -Count 500 | Copy-Item -Destination "C:\Users\flare\Downl

ads\benign"i.e., get all files that contain the .exe extension, recursively, then pick and copy 500 random samples into a folder.

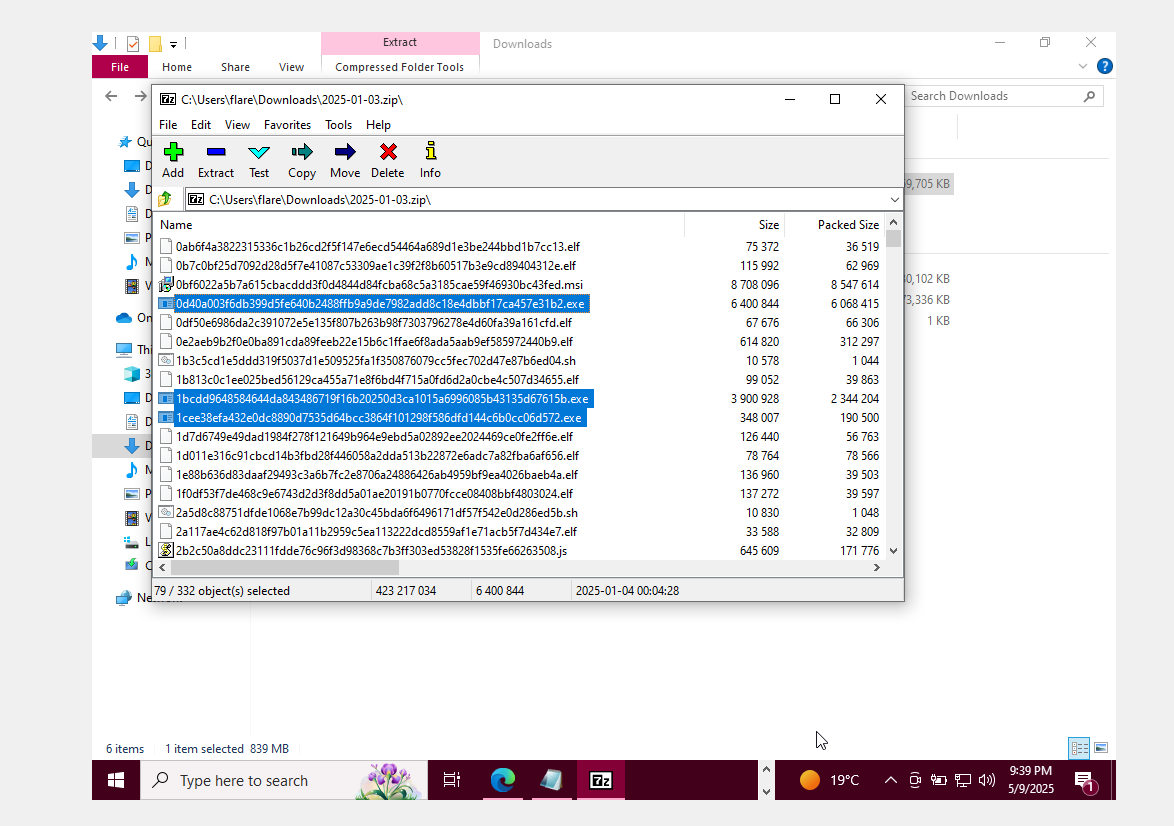

Malicious samples were sources from online malware repositories and databases, namely GitHub (shocking!) and MalwareBazaar↗. Obviously not all executables are guaranteed to run due to software architecture and OS compatibility. Hence, this project's scope is limited to DOS MZ (.exe) executables aimed at Windows machines.

Feature Extraction: Static Features

Given an executable, without running it, the program can ba analyzed based on its static features; i.e., features that can observed directly from the file. For example, if a program claims to be a simple single-player game, and it requires cryptographic and networking functions (as declared among its imported libraries), then it is a cause for concern. For each and every executable, we extract its imported libraries, number of sections (and existence of non-standard sections), entropy (randomness), and determine whether or not it is packed (i.e., if it contains artifacts from known packers).

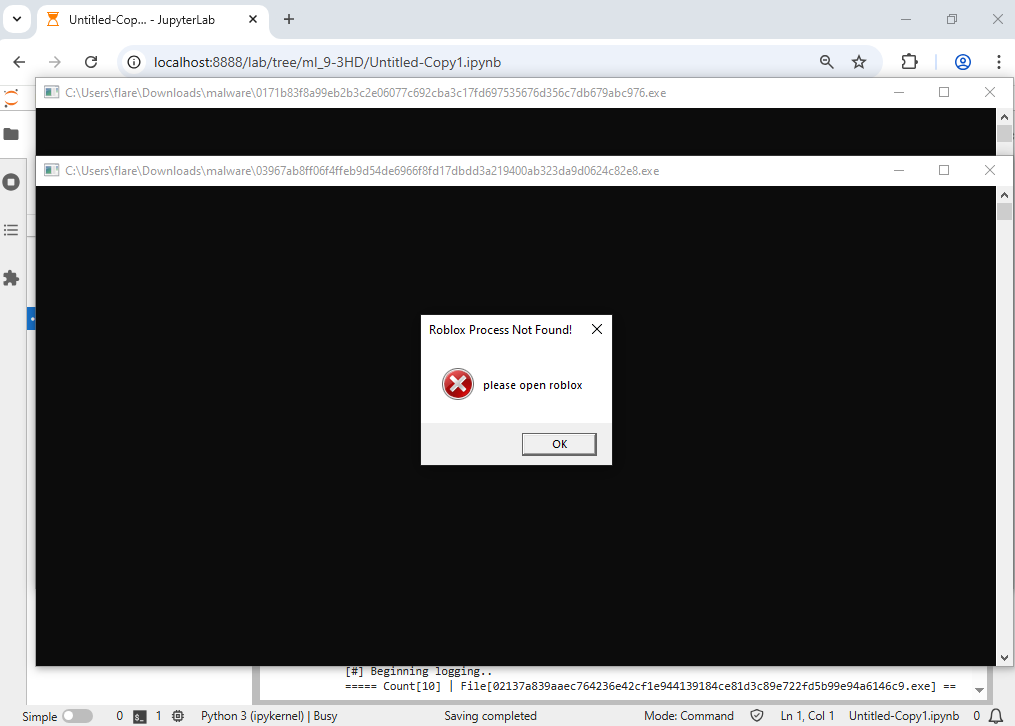

Feature Extraction: Dynamic Features (+ running malware!)

Now for the fun part. Static features are one thing, but what is most telling is revealed when you actually run the executable. The answer to how we map and measure dynamic (i.e., runtime) features is to track what specific API functions are being called upon startup. For example, say two programs, one benign and the other malicious, requires time functionalities. However, on startup, one of them is set to wait for 60 seconds before fully executing - this is a common evasion tactic.

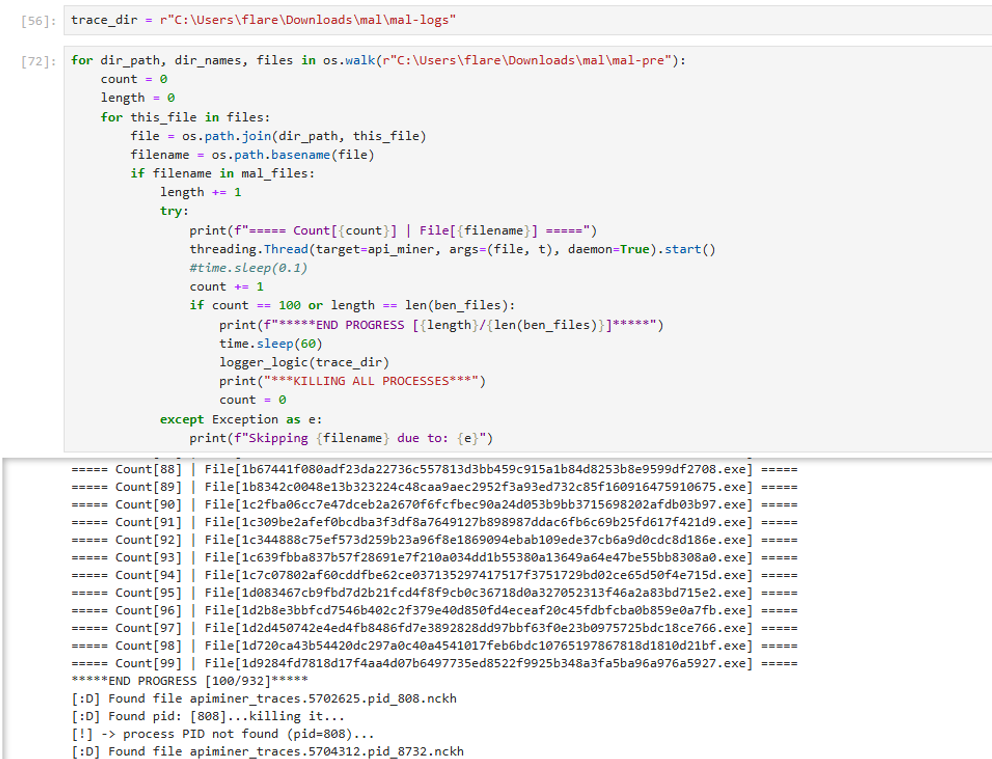

APIMiner is the perfect tool for the task, however running this many samples requires automation:

Running hundreds of malware samples is never a good idea, as it may crash one's virtual system. The solution to this is to run the samples in batches (in this case, of 100), with each sample running on a tracked thread. Their API calls are recorded via APIMiner into individual text files. After 60 seconds of runtime, all active malicious processes are forcibly stopped, and the next batch is processed. This ensures that each program is given enough time to run.

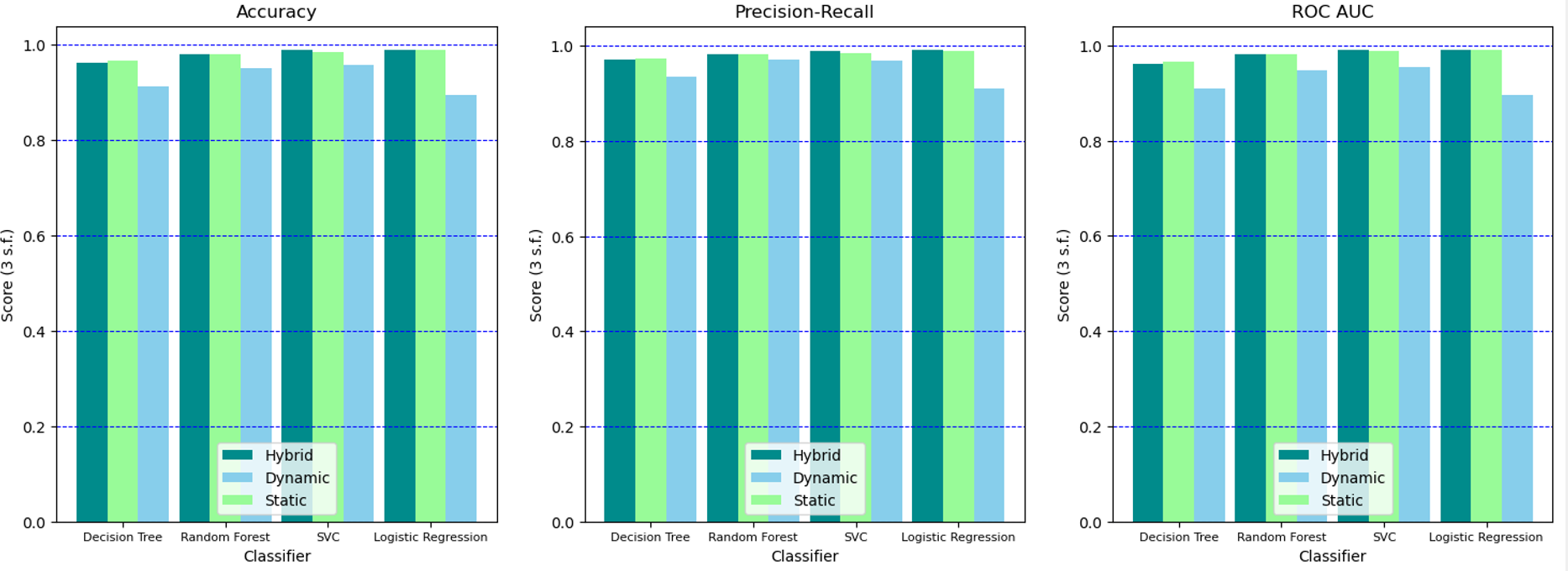

Machine Learning

Both static and dynamic features are combined into a hybrid dataset. A train:test ratio of 0.7:0.3 is used to evaluate 4 classical statistical classifiers: Decision Tree, SVC, Random Forest, and Logistic Regression. SVC was the best performer overall.

Data

Please read the following report↗ for a more detailed writeup of this project.

References

[1] Dr Josh Stroschein - The Cyber Yeti, “Building a VM for Reverse Engineering and Malware Analysis! Installing the FLARE-VM,” YouTube, Feb. 29, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i8dCyy8WMKY (accessed May 5, 2025).

[2] Flare VM. "flare-vm", GitHub, Oct. 25, 2021. https://github.com/mandiant/flare-vm (accessed May 5, 2025).